Lots of authors have "day jobs." This is because writing books really doesn't pay well, unless you're a prolific bestseller like Stephen King or you write a runaway hit like Stephenie Meyer. In perusing forums, a hobby that's eating away at much of my free time, I've discovered that many indie authors dream of the day when they can become full-time writers. But be careful what you wish for. It's time to find out what it's like to write full-time.

Writing All the Time

I am a full-time writer, and it's not glamorous. It's not even convenient. What's it like to write full-time? It's like having 5 different parents, or rowdy children, demanding something from you every single second. And it's a whole lot like staring at a screen for 12 hours a day, 7 days a week. Out of the 80-plus hours you spend writing in a given week, you're incredibly lucky it you get to spend 5 of them writing something you actually want to write.

Many full-time writers are freelancers, like myself. Many of them receive income from several different sources, and continuously seek out new freelance opportunities. I currently work regularly for three different outfits on strict deadlines, irregularly for another outfit on very tight deadlines, and two others whenever the wind blows. That means I may do writing work for up to 6 different employers during any given week, and any of them may come back with rewrites. Sometimes they might even do it on the same day -- like Friday, around 5 in the evening. Lots of times, they want what they need ASAP, and give me a 24- or 48-hour deadline.

I write, on average, 5 to 10 different pieces a day ranging from 250 to 1000 words in length. Out of those 5 to 10, I might get to choose the headline and all the content for the entire piece twice. The other three to eight times I start writing something new, I'm writing what I got told to write...and even on those two I might get to choose, there are very strict formats and requirements I must meet. Sometimes, even the words are chosen for me. My job is to put them in a reasonable sort of order. I don't always get to insert amusing anecdotes, and many times I might not be inspired to write one anyway. The tone I write in might also be chosen for me, until very little of my own native writing voice remains.

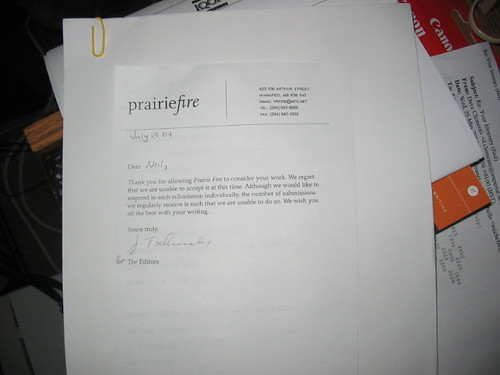

In other words, it's a job. The writer who writes full time still has a boss -- and it's quite likely that they have several. Editors are persnickety, and sometimes vague, and there will be times when you wish a reviewer would come along and tear your indie book apart before you have to rewrite this how-to article even one more time. Sometimes it's scary. A gig that seems solid might change all of a sudden, because a website got bought out or an editor got fired or a search algorithm on Google got revamped. Suddenly you're making less money, and everything is insecure. Then tax time comes, and real terror enters your life. And while you're typing away 80-something hours a week, everyone around you will actually get to have a life.

Often, you'll be lonely. You're staring at a screen all day, writing about dull subjects with words you don't even get to chose and answering to editors who may only address you as "freelance writer." You'll get the feeling that you're replaceable, and you'll get a taste of the massive competition out there every time you reply to another freelance job opportunity.

But you'll be a writer, using your words to make a living. Every once in a while, you might have the chance to revel in that. It's kind of fun when you say that you're a writer to someone who doesn't realize how really un-glamorous it all is.

Writing all the time is just great, until you've actually got to do it to keep food in your belly. Then it gets annoying, and scary...and lonely. If wrecking your eyes and answering to too many bosses is your idea of a good time, you're ready to do it.

However, know this: when you write full time, you have to make an effort to keep loving the act of writing. When it goes from hobby to job, things change...and writing can be very, very hard to love then.