Some books are so good, they can't be adapted only once. They come around again, and again...and again and again. And while I'm not an expert on the book version of Little Women, having read it once and not liking it very much, I am an expert on the various film adaptations that followed -- and I'm about to save you 800 pages of reading.

The Book

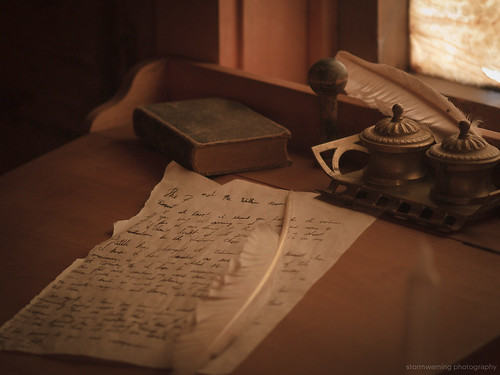

Louisa May Alcott based

Little Women on her own home life. Like the character Jo, Louisa had three sisters and lived in her family home, Orchard House, in Concord, Massachusetts. And it is a

ponderous book, so big in fact it was published in two volumes in 1868 and 1869.

Little Women follows the lives of sisters Meg, Jo, Beth and Amy, the March girls, and it was an immediate hit among readers. Margaret March, or Meg, is the oldest and quite a beauty. Meg is a perfect little lady, with a pretty face and pretty manners to match. She is something of a substitute mother to the others, assuming control of the house when their mother, Marmee, is not around. Marmee is often busy with charitable works, because the Civil War is raging. It's because the war that the girls' father is not home; he's a Yankee chaplain.

They're quite poor, but they are a well-respected family and the girls have been raised to be ladies. It's worked, for the most part -- except for Jo. The tomboy of the bunch, Josephine March is rambunctious and not at all a fan of being a little lady. She would rather be in the war with her father than sitting at home with her sisters, but it's not an option. Jo also has a quick temper and a ton of creativity; she has literary aspirations, and often leads the others in very inventive play-acting.

Elizabeth, Beth, is painted as something of a saint. She is musically gifted and painfully shy. Beth never desires to go to parties or even go outside of her home, preferring to stay around people she knows than those she does not. She's so good she's unbelievable, in fact. At one point in the book, Beth nearly dies of scarlet fever. Jo painfully nurses her back to health, but Beth is not long for this world after her brush with death. Eventually she dies in quite a serene (and wholly unreal) manner, passing away like an angel. Alcott's metaphors are heavy throughout this part of the novel, and she even borrows from the Bible to make her point.

Amy is the youngest, and artistic by nature. She very much wants to have more than she does and is very much focused on becoming better than she is. Amy loves using big words and trying to make other little girls jealous, activities which have a way of turning out poorly for her. Amy is spoiled, and of all the sisters has the most trouble getting along with Jo.

Jo meets and befriends their new neighbor. His name is Theodore Laurence, but he is often addressed as Laurie or Teddy. She brings him into the girls' play, and he often calls her a "good fellow" and similar friendly names. But as time progresses, the nature of Laurie's feelings change for Jo and he begins to fancy himself in love with her. When it becomes clear that Meg has eyes for Laurie's tutor, Mr. Brooks, he makes his move on Jo by proposing marriage.

She rejects him, and he leaves their friendship, the state and the country. Laurie goes abroad, to Europe, in an apparent attempt to escape his broken heart. Jo decides to pursue her literary ambitions and goes to New York. Amy is sent away during Beth's illness and becomes a companion to rich old Aunt March, who is very disapproving of her little brother (Jo's father). The two become close, and Amy goes to Europe with Aunt March to study art as a result.

In Europe, Amy re-connects with Laurie, and the two actually begin courting. By the time Amy returns to Orchard House, she is ready to become Laurie's wife. Meg, who has married John Brooks, delivers him two healthy babies. The war is over, and father has returned home. But Beth is gone, and Jo is once again at odds upon returning from New York. A man she met there, however, comes to find her to tell her that the publishers have accepted her book -- a book about herself and her sisters -- and Jo realizes her love for him. The two marry, and Jo has inherited Aunt March's old home. They decide they will turn it into a school.

Everyone lives fairly happily ever after, and you can read all about it in the sequels Good Wives and Little Men.

The Films

I know all of those details not because I've made a thorough study of the book. It's because I've seen the important adaptations. Honestly, I could barely get through the book version of Little Women. It's full of flowery language, it's incredibly thick and by today's standards the language feels archaic. But on film, the story is truly exceptional...if you're watching the right film (and you probably aren't).

The first film major adaptation of Little Women was created when the movies were still young. Directed by the legendary George Cukor, it had absolutely everything going for it. Two previous versions of the book were made into silent films in 1917 and 1918, but neither of them had Katharine Hepburn in them.

This one did. She played Jo, of course, and was age 26. Amy March was played by a 23-year-old Joan Bennett (pictured above). Jean Parker as Beth was 18, and Frances Dee as Meg was 23 -- younger than Hepburn. But Hepburn is fantastic as the brash Jo March, and she shines on the silver screen. In this version, Meg works as a seamstress (not a governess) and Beth plays a clavichord and not a piano.

The critics adored the film, which quickly glossed over Beth's illness and death and barely even paid lip service to Laurie's broken heart. It focused on the prettier aspects of the story instead and kept the focus on Hepburn in every scene, so the story is Jo's more than ever in this version.

It's quite a good version, and decently faithful to the book...but it isn't the best. That was made 15 years later.

My favorite adaptation of Little Women was released in 1949, and contains a star-studded cast. It's done in full Technicolor glory, and stars June Allyson as Jo. At 28, she was really much too old for the role...and it's only one of multiple casting problems you'll find in the flick.

Beth is played by popular child actress (at the time) Margaret O'Brien, who was much younger than the big star the movie nabbed for the role of Amy (that would be Elizabeth Taylor, who looks great as a blonde). Beth is supposed to be older than Amy, but she became the youngest sister as a result of this casting decision. During filming, O'Brien was only 10 years old. Elizabeth Taylor was 21. Janet Leigh, who would go on to become a scream queen thanks to her role in Psycho was 24 when she played Meg. The famous silver screen queen Mary Astor is also in the film as Marmee.

Jo does not meet Laurie as a holiday party, as she does in the book, but actually goes to his home to meet him for the first time. The Christmas party happens later, and all four of the March girls go (only Jo and Meg went in the book).

The pivotal scene where Amy falls through the ice while skating is cut completely, though in the book it's important because it brings Jo and Amy closer together. Amy's romance with Laurie is also cut out of this version of the film.

So why is it my favorite? Because June Allyson was made to be Jo. She's absolutely perfect in the role, lovable and brash and bold all at the same time. Not to mention, the costumes look incredible in this version.

Another version of the film was made in 1978 with Meredith Baxter and Susan Dey, but I've never seen it. I have seen the much more recent adaptation, which is probably the most well-known. Like the '49 flick, it contains a star-filled cast.

Released on Christmas Day, the 1994 version of Little Women has been seen by many millions. The cast was packed with big names and no expense was spared on the costumes, but it's still not the best version. The 1949 joint is -- trust me.

This time, Winona Ryder plays Jo March. Claire Danes is Beth, and in the beginning Kirsten Dunst is Amy. Susan Sarandon nabbed the role of Marmee, while the boy who would be Batman, Christian Bale, plays Laurie. Eric Stoltz, of '80s movie fame, is John Brooke. Danes does an absolutely brilliant job as Beth; I can't get through her final scene without crying. But Dunst, who was still very young at the time, turns Amy into a screaming and hysterical wreck. Ryder is far too reserved to be Jo, and next to her Susan Sarandon doesn't feel convincing at all. Samantha Mathis becomes older Amy March, and she's even worse than Dunst. However, the film did land Ryder a Best Actress Oscar nod, so clearly the critics don't agree about the casting.

What Got Adapted?

The 1994 version of the book had too many stars. Claire Danes doesn't get the opportunity to do Beth much justice, and her shyness is really underdeveloped. Beth never overcomes her own worst fears to thank Mr. Laurence for the piano, and his character is pushed far into the background. Ryder's subdued Jo doesn't shout "Christopher Columbus" or any other colorful swears, and this Jo never laments the fact that she can't fight in the Civil War (scenes that Allyson's Jo captures beautifully). Meg never has her big awakening regarding her own love for Mr. Brooks, which does happen in the better 1949 version, in 1994. And in 1994, we never see Amy wearing the clothes pin to make her nose straight. The big present-giving scene with Marmee is also skipped in the newest version, and Jo never really learns her lesson after Amy falls hrough the pond.

The 1949 version also features more of Jo's struggles as an author, something that is barely in the 1994 version and is only mentioned a little in 1933. Casting problems aside, it's simply the best adaptation of the story and the one you ought to see -- especially if you don't plan on reading the book.