Even if you haven't read it, or seen it, or pulled down your grandmother's curtains and paraded around the house (what? I didn't do that), I know you've heard of it. It's Gone With the Wind, and it's both a literary and film juggernaut that you just can't stop -- not even 75 years later. It also happens to be my personal favorite, and it's why I'm making it the first selection for the new Books on Film feature.

The Book

Gone With the Wind was published in 1936, and it was most definitely an immediate success. It was already a bestseller before the reviews appeared in national magazines. Almost instantly, author Margaret Mitchell was awarded the Pulitzer and the novel's film rights were snapped up by one David O. Selznick (more on him later).

Set in the south during the Civil War and the Reconstruction era that followed, Gone With the Wind revolves around the life of Scarlett O'Hara. It's not often called a coming-of-age tale, though that's exactly what it is. Scarlett becomes shrewd and hardened during the war, the whole of which she spends pining away for a man who is married and who does not love her romantically.

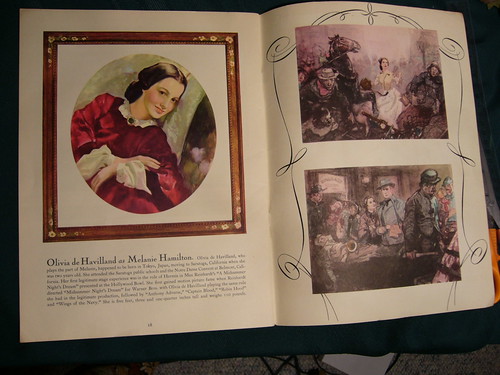

Rhett Butler, the book's hero (or maybe anti-hero), is passionately in love with her. But Scarlett, obsessed with Ashley Wilkes, doesn't really care. She loathes and envies Ashley's tenderhearted and loving wife, Melanie. For spite, and to make Ashley jealous, Scarlett marries Melanie's brother Charles. After he dies in the war, she marries her sister's somewhat long-in-the-tooth beau Mr. Kennedy. It isn't until he dies -- arguably, because of Scarlett -- that she finally condescends to marry Rhett. He does all he can to please her but it's never enough, and when Melanie dies he finally decides he's just too fed up with his wife to carry on. Besides, she'll certainly be running after Ashley harder than ever now. So Rhett leaves, and in one of the most climatic and tragic scenes ever written, Scarlett O'Hara Hamilton Kennedy Butler realizes that she really loved Rhett all along, and Ashley could never be a decent companion for her. She runs after Rhett, but it's too late...and he walks out. The book ends, as does the film, with Scarlett's iconic line: "After all, tomorrow is another day."

Try not to judge the book on my brief summary; it took Mitchell over 1,000 pages to describe these same events, which she does much more wonderfully and poetically than I.

The Film

Upon purchasing the rights to the novel in 1936, David O. Selznik immediately went to work. He started taking meetings with Hollywood's biggest stars, both male and female, though from the outset public opinion was quite strongly settled on one actor, and one actor only, for the role of Rhett: Clark Gable. Debonair, drop-dead handsome, and oozing masculinity through ever pore, Gable was pretty much Selznick's first choice, too. Gable didn't want the role. Through much negotiation and deal-making, he was secured to play the part. The search for Scarlett would span two years and two continents.

Half a world away, a London stage actress named Vivien Leigh was also in love with the book. She told a friend as early as 1937 that she would play the role on film, but she had some extremely stiff competition. Just about every actress in Hollywood with any box office value screen-tested for the role, and Bette Davis rabidly coveted it. But Leigh was also on her way to Hollywood, and through her various connections scored an introduction to Selznick through his own brother, a well-known agent at the time. On the night when the studio burned up several massive sets used in former productions, to film the epic scene when Atlanta burns to the ground in the film, David O. Selznick met his Scarlett O'Hara. Leigh was introduced by this name, and after her screen test the producer was convinced.

Selznick was well-known for doing book adaptations on film, and he'd earned a reputation for staying true to the author's original work. But Gone With the Wind was a 1,000-page monstrosity covering years and years of truly epic history, and the project became overwhelming right away. By all accounts, Selznick was a veritable madman on set. He oversaw every single stage of the production, and it created some tension. One person involved with the film complained that everything had to be done and re-done again.

The opening scene alone was filmed four times, complete with costume changes and location changes, before it was finally deemed fit for the flick. Two directors were fired, one was re-hired, and Selznick edited the movie in full at least twice. The way the story goes, studio representatives literally had to take the reels for the film out of his hands because if the movie was delayed even one more day it would miss its premiere date.

Selznick's obsession and attention to detail paid off. Gone With the Wind became the highest-grossing film of all time, in its day, and remains in the top ten of the American Film Institute's Greatest Films of All Time. It has been released and re-released endlessly, in every possible format, and you can still catch it on television at least once a year. The movie practically swept the Oscars and made a quick star of Vivien Leigh. Fashion trends immediately developed, and anything associated with Scarlett O'Hara was an instant hit in the late 1930s and early 40s.

But any movie can be popular. The real question is: did Selznick succeed? Did he transform a massive book into a marketable movie, without too much loss of story?

What Got Adapted?

My verdict: yes. Now that's a controversial answer, because the film version of Gone With the Wind is certainly missing a ton of story elements. In the book, Scarlett has multiple children. In the film, there is only one. The movie also leaves out a huge chunk of the story that revolves around Scarlett's family; both her sisters come to rather ill ends, and movie watchers won't ever know of their tragic fates. Much of what happens to Scarlett in the years immediately after the war is skipped over quite neatly by Selznick, though that could be due to the fact that the original scriptwriter was fired. A parade of successive writers came along behind him, until he was eventually re-hired to clean it all up (the list of people who were fired from Gone With the Wind is quite impressive).

However, Gone With the Wind has a mind-numbing running time of 3 hours and 44 minutes for a good reason: a strong effort was made to capture the whole story. When you adapt a gigantic book, you end up with a really long film. The flavor and major plot points of the book are most definitely captured by the film, the actors are all well-casted and very suited to their roles, and despite the omissions of the more racy material that the book doesn't shrink away from, what's left unsaid in the movie is still pretty clear.

For a book on film, Gone With the Wind is one of the best adaptations you can find. The movie does just what it's meant to do: it turns text into live-action images. There are some discrepancies, of course. According to legend, while Margaret Mitchell and her husband watched the film for the first time, he turned to her during the famous train station scene and remarked, "If we had that many soldiers, we would have won the war!" But overall, it remains one of the best examples of a book on film and it's well worth watching.